Engaging with hard-to-reach and potentially vulnerable participants in the AP4L Project – Part II - Workshops

By Dr. Ryan Gibson and Prof. Wendy Moncur

Introduction

AP4L’s overarching goal is to develop privacy-enhancing

technologies (PETs) that support people undergoing a significant life

transition to be safer online. The first step in building PETs that make a real

difference is to understand what these people do online and the subsequent

challenges they face. Central to this process is the involvement of

participants from the four populations we are exploring in AP4L - Leaving the

Armed Forces; LGBTQIA+; Living with Cancer; Relationship Breakdown – who can

share their lived experience of transitioning online.

These experiences may then be translated into design

requirements for the development team to generate PETs that more accurately

reflect the transition activities being conducted online and the related

privacy risks and harms that people encounter.

Nevertheless, designing and recruiting for research

involving people who have undergone a life transition is extremely difficult.

For example, protocols will centre on sensitive and possibly distressing times

within an individual’s life that potential participants may feel uncomfortable

reliving/discussing without an established relationship with the research team.

This blog post provides insights into the methods used to maximise engagement

with our target populations, along with the barriers we encountered with a set

of workshops.

Workshop Design

On completion of the survey that was discussed in the first

blog, we were left with various research questions that could not be

answered comprehensively by the data collected. As such, we decided to design

and conduct ‘creative security’ workshops that delve deeper into the online

privacy experiences of the four transition groups. These workshops were

subsequently designed in two phases. First, we explored the literature to

identify potential methods that had been proven effective in research involving

the four transition groups. Suitable methods were adapted to fit our research

questions, as well as the potential accessibility needs of participants, before

being piloted with the PIP panel to judge their appropriateness and make final

adjustments. The result was a workshop protocol that lasted up to 3 hours and

could be conducted in person or online, in one go or over a multi-day period.

Up to 8 individuals from the same life transition would be involved in a single

workshop. Online participants were offered the opportunity to contribute

anonymously by changing their names on the video conferencing platform and

keeping their cameras/microphones turned off. Both online and in-person, the

participants were guided through the following four tasks by an experienced

facilitator, who is accompanied by a note-taker and a colleague responsible for

monitoring the well-being of the participants:

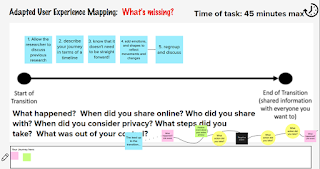

(1)

User Journey mapping, where the

participants draw a timeline of how their transition played out online, marked

by both positive and negative events;

(2)

Empathy mapping, where the participants

dig more into what they have done online, who they spoke to, what they

discussed, the harms they experienced, etc.

(3)

Metaphor card sorting, where the

participants are introduced to some of the life experiences shared in the

survey and asked whether they relate to these experiences. In addition, they

are encouraged to discuss potential technologies that can support individuals

in similar situations to protect their online privacy.

(4)

MoSCoW (Must have, Should have, Could

have, Won’t have) Prioritisation, where participants are asked to

propose and rank features to include in future privacy-enhancing technologies

related to life transitions.

Fig 1: Screenshot of online workshop tools

Workshop Recruitment

Our target n-size for the workshops was 16 participants per

transition group, to ensure we identified individuals with a range of privacy

experiences. Yet recruitment across each group has been challenging. To date,

34 participants (53%) have completed the workshop: ten people Living with

Cancer; nine who identify as LGBTQIA+; eight who have Left the Armed Forces;

and seven who have experienced a significant Relationship Breakdown. We have

utilised a range of recruitment avenues to try and maximise engagement, each of

which had advantages and disadvantages. These are summarised in the table

below:

Table 1: Recruitment channels used, including their

advantage and disadvantages

|

Recruitment Channel |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Research Team and project partners

(e.g. LGBT Foundation) professional social media channels. |

Able to reach a wide range of

participants from a specific transition group. |

Engagement is quite low. We also

received a large amount of bot responses, some of which were extremely

sophisticated and likely to have been generated by large language models such

as ChatGPT. Bot responses were particularly frequent on X (formerly Twitter). |

|

Closed peer to peer support

groups on social media. |

Guarantees recruitment of

participants who seek support online for their transition. |

Peer to peer support groups are

difficult to gain access to for researchers. Moderators frequently turn down

requests to post a recruitment advert since it breaks the purpose of the

group. |

|

Local posters and charities. |

Higher likelihood of hosting an

in-person workshop. Greater control over who participates by discussing

inclusion criteria with charity gatekeepers. |

Requires significant effort to

generate trust with the charities prior to them facilitating recruitment. Not

all charities are open to, or have the capacity, to help. |

|

A cheaper alternative to

Prolific that provides access to a wide range of registered users. |

Unlike Prolific, you pay for the

number of participants who sign up for a study as opposed to those who take

part. The percentage of individuals who progressed from sign-up to

participation was extremely low. Just 4 out of the 40 individuals who agreed

to take part completed the workshop (10%). |

We are currently working with the PIP panel to identify new

recruitment channels, particularly charities local to them in which they may

have received support from.

Observed advantages and disadvantages of in-person and

online workshops

Overall, gaining access to those who have lived experience

of the four transition groups has been a challenging process. Despite this, we

believe that the flexibility of our workshop protocol has actually increased

the accessibility of our study for potential participants. For example,

in-person workshops, in which recruitment was facilitated by local charities,

provided the opportunity for individuals from the same support networks to come

together and share their deeply personal experiences in a safe space. This led

to more spontaneous discussions taking place, that extend beyond the questions

embedded within the workshop tasks. Nevertheless, as described above, a great

deal of effort is required to build a relationship with local organisations,

and subsequently potential participants, before enough trust is developed to

enable individuals to comfortably share their life experiences.

Providing an online alternative alleviates the need to

establish a prior relationship with participants, since they have the option to

attend anonymously with both their cameras and microphones turned off. This may

put them at ease sooner. In addition, virtual workshops make it easier to

recruit enough numbers to run a study, since we are not restricted to a

specific area within the UK. However, we have found that online participants

have struggled to adapt quickly to the software being used to run the workshop

(mural.co), and therefore tend to focus on

completing the set tasks, which limits spontaneous engagements with other

individuals.

Conclusion

This blog post has discussed the importance of involving

hard to reach and potentially vulnerable populations within research to ensure

outcomes better meet their complex needs. In addition, we have introduced the

methods used in the AP4L project to enhance engagement with four life

transition groups - Leaving the Armed Forces; LGBTQIA+; Living with Cancer;

Relationship Breakdown – to support other researchers in working with these

populations.

Comments

Post a Comment