Introducing the need to use Technology as a Tool, and not as a Master

Karen Renaud (University of

Strathclyde – karen.renaud@strath.ac.uk)

Michael McGuire (University of Surrey - m.mcguire@surrey.ac.uk)

We have all been horrified and saddened as the full story of the Post Office case has unfolded in the public domain. We hear about harms to sub postmasters, to their families and their health and we wonder how it was possible for this injustice to occur at such a scale.

Many are pointing to the kinds of collusions which have typically characterised the ‘crimes of the powerful’. The lies, the evasions, and the brazen cover-ups on the part of post office managers, the abject failure of politicians to exercise due diligence and the rewards given by the establishment to those who treated the postmasters so appallingly. However, there is a bigger picture that also needs to be considered, which we call out in McGuire and Renaud (2023).

Technology powers everything we do: airplanes, devices we use to communicate globally, and our home appliances, to mention just a few. We, as a society, have embraced the convenience and functionality offered by technology, but very few people understand how it works, even fewer understand that technology is not infallible and far fewer still appreciate the subversive power technology has acquired to regulate our lives. Fundamental to this hegemonic technological order is an unquestioning docility, one spawned by a shift in the very way we think about the world. What the great theorist of technology Herbert Marcuse termed ‘technological rationality’ is nothing less than a cognitive colonisation, a reshaping of our minds along technical, rather than human lines.

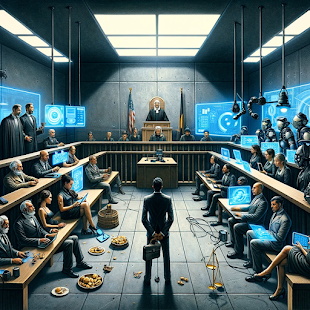

In reality technology is often faulty. In the Post Office case, critical flaws mounted in its much lauded Horizon system, generating spurious transactions and inaccurate balances. But the influence of technological rationality blinded the priesthood of experts responsible for Horizon who should have known better, rendering them incapable of seeing what was in front of their eyes. As a result of their unquestioning faith, many innocent parties were prosecuted and incarcerated, on the basis of nothing more than a number displayed on a computer screen and without any of the kind of corroborating evidence required in traditional processes of justice. Scepticism and informed judgement departed, and blind faith ruled. The immediate result was one of the largest miscarriages of justice in British history. But the wider tragedy was the damage done to our justice system as it too became a handmaiden to the imperatives of technology.

Flawed software has led to a

number of undesirable outcomes in other domains. For example, a mistake

by a facial recognition system led to an unsafe arrest and incarceration. A

software

fault enabled a bank heist in Bangladesh . A lack of safeguards led to a false

missile alarm in Hawaii. A quick Google search returns many more examples.

The Post-Office scandal should come as a warning to us all that we are at a crisis point in our relationship with technology. Especially in an era when Artificial Intelligence threatens to render us still more impotent as it pervades all our organisations and hollows out our justice systems. The time has come when we, as a society, have to make some hard choices and to substitute convenience for a new scepticism about the mixed blessings of technology. Effective checks and balances are required to ensure that software systems are used as tools, not as masters. As tools, combined with a “trust but verify” mantra, they can make a significant contribution. As masters, they will lead us into a dystopia that no one wants.

Some links:

Paper: McGuire, M. R., & Renaud, K. (2023). Harm, injustice & technology: Reflections on the UK's subpostmasters’ case. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 62(4), 441-461.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/hojo.12533

YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2PgX3bqpJKc

Comments

Post a Comment